things hidden

Posted on June 5, 2020

There are the things that are out in the open, and there are the things that are hidden. The real world has more to do with what is hidden.

— Saul Leiter

It’s been a bleak time. Last summer, my dad died. Set against the backdrop of the grander world stage – a stage in flames – it is a small grief, maybe. But it is my grief. I have written something about him and when I have found some courage, I will post it, but for now: small things. Beacuse the small things reveal the big things; the sum of their parts. The things that give us meaning. I picked up a camera for the first time in a long, long time last week. It was my dad’s camera. I felt it in my hands. Solid. Weighty. I thought about all the times he had picked it up. I imagined his big hands wrapped around it. His eye, seeking out moments. Sweet bursts of joy.

It was dawn. I was looking for some light.

© Emily Hughes, 2020

into the wild

Posted on July 2, 2019

A couple of months ago, I was out for or a walk in the countryside with my family. It was a leaden, dreary day, much the same as many we had been having for what seemed like weeks on end. We were all a bit fed up and long anticipating the technicolour hues cast by the broad stroke of spring’s sunshine.

A raw wind cut across our cheeks as we walked. I watched the red kites circling, their long low whistles filling the empty skies. I watched them swoop down to feed on some lone unidentifiable hunk of carrion, its inards spewing out into the middle of an open field. We walked past another field, stinking and ripe with streaming rivers of cow dung. Well, it has to go somewhere, I thought. A pungent pastoral vignette. Nestled in amongst some hedgerow and dour grey-barked beech trees, a blackbird’s head, ripped from its body. My children climbed and explored the carcass of a old oak tree, its skeleton smooth and worn. Once no doubt grand and proud and stately, it lay, finished, horizontal, roots long since ripped from the earth.

Dirt and decay and excretion. Life and death. Nature survives, and there is drudgery and violence in that.

Like us, nature is weary. It is not always beautiful or romantic.

Sometimes it is positively unwelcoming.

As much as I love walking in and photographing woods and forests, jungles, I also find them menacing. Maybe its because of all those fairytales: innocent children lost, eaten, sexual transgressions, transformations. Murder. After all, anything can happen in the woods, set apart as they are from the boundaries of of society and morality. Able to provide cover for the things we don’t want other people to see. As we walked we came across remnants of the thrill of illicit activities: empty lager cans, a vodka bottle, used condoms. A pair of knickers hung on a tree.

The woods have their own set of rules.

I never walk alone in the woods. Whilst I am happy to play the flâneur in cities, loose myself, find something new, I would not do this in nature. As someone who runs regularly, I am careful to stick to known paths. Maybe I shouldn’t be so afraid, but there are too many stories out there, even in the leafy suburbs of Berkshire; stories which are fact, not fiction, and I am too aware that my gender can be vulnerable in certain situations and that the trees, though beautiful and strong, would not move to save me if they heard my cries. They are immovable, impassive to our human struggles.

After all, nature is cruel. It is hostile.

But it is also vulnerable.

That same weekend we went for our family walk, an unassuming-looking vehicle parked up at the end of our road. Tree Surgeons, I saw painted on the side. It was Saturday morning, everyone busying about with their weekend plans. Three men in yellow vests with chainsaws hopped out and set about attacking a plot of land next to the railway bridge. This plot of land is privately owned, fenced off by railings. People pass it when they walk over the bridge used as a cut-through into town. It was undisturbed for many many years and as a result had become a seething, dark and gnarling mass, dense with vegetation. Impenetrable. As such, it was wild in the purest sense. It hummed with life, untouched, undisturbed. Unknown. Not only trees and garden birds, birds of prey, but also the furtive, inroverted kind like slow worms and stag beetles and probably hundreds more species besides.

In less than 48 hours it was gone. Razed to the ground.

I watched the relentless chipper turn the trees to sawdust. I listened to the drone of destruction from my bedroom window. Messages from concerned residents flew about my inbox: What on earth is going on?

The destruction was bloody. Brutal. Absolute. There was a desperate, manic air about it which felt ominous and disturbing.

On Sunday evening I went outside and surveyed the wreckage. I sniffed the air, and I smelled greed in it.

‘Maybe it will be something wonderful?’ one peppy resident wrote hopefully. I could almost hear the cries of perturbation as I scrolled through the email chain: talk of phone calls to the council, protected trees, breaches of preservation orders, aroboratorial officers, nesting Kites, the RSPB, land surveyors.

We all knew it would not be something wonderful. After all, what is now gone was the something wonderful.

Now, when people walk over the bridge, they see a graveyard, although two months on it has started to grow green again; life is slowly returning, though we all know it will not be for long. Razored tree branches jut haphazardly from the ground like ancient stone pillars. Jagged grave markers. A covering of twigs and branches strewn across the ground like skeleton bones.

On the Monday morning after the massacre, I watched the birds, frantic, confused, searching for their homes.

The land – prime real estate – will be sold, built on eventually. It will be luxury flats or a couple of top spec houses. But my heart weighs a little heavier in its cage for the loss of something I never much considered before. And what lies in its place is a reminder of that something wonderful. It is like looking upon a gaping wound.

*

Last year, whilst on holiday visiting the jungle terrain of Tamin Negara in Malaysia, we took took a hike through the ancient forest we were staying in. The flanks of the older trees were giant-like, impressive in their broad girth, bark-skin folded over, gnarled and wrinkled with age, purlicue spanning the ground and snaking into a writhing nest of roots, meandering wide and deep into the earth.

I did actually get lost – briefly – in the hot, thick undergrowth of the sauna-jungle. As I soon realised I didn’t know where on earth I was, my heart started to beat faster, drumming loud in my ears and against my chest. The humidity seemed to intensify my fear and my clothes stuck against my skin, slick with sweat. I knew there were leaches and deadly spiders and scorpions that glowed in the dark. As I turned down twisting paths I encountered camouflage trunks and tangled vines and jagged fronds which scratched my face and seemed to close like broken fingers around me, and the winding snake-roots tripped me up as mosquitoes and other biting insects danced around me. My hands were clammy and my head was fogged up; condensed with a close, drenching heat I wasn’t acclimatised to. There were strange, vociferous noises, birds or other unfamiliar creatures I couldn’t identify. Nothing like the gentle twittering of English garden birds or the screech of a fox in the back garden which I once mistook for a changeling’s cry. I remembered the story I had read about in a museum, a man living in the plantations in the Highlands when the British first colonised Malaysia. He had often wandered in the forest, but one day he got lost and never returned. His body was never recovered. A mystery. I wondered, was this the forest responding, staking its claim. I wondered how many acres of forest had been destroyed to create this lush landscape, gentle swathes of green-tipped hills. As I wandered, lost, I imagined naked tribesmen roaming about with poison-tipped spears. Everywhere I turned the forest seemed to invite me in, then block my way. It seemed to say: Come, but you are not welcome here. You are not one of us.

Except, I was not really in any danger, though the fear was real, primal, it was misplaced. I soon found other people who pointed the way back to the meeting place and suddenly the jungle did not seem quite so scary anymore. Because now the forest has signs and green guides and paths and a treetop jungle walkway. You can walk through the canopies. Though the indigenous tribes (Orang Uli) are still there, they are a tourist attraction and they demonstrate their fire-making techniques to citrus clouds of sweaty tourists, using teddy bears as targets for their blowpipes. They still dip the darts in poison, but only for the animals. You can wander around their villages and take pictures of their washing lines and their wooden huts built on stilts and thatched with jungle grasses. You can even sleep in their village for a more authentic experience. And even though the men and older boys do still hunt, it is more out of pride and tradition; they buy their food – mostly tins and packet food – from trucks, mobile shops, which visit their villages regularly. The jungle no longer sustains them.

You see the men, red-eyed, laughing and joking. At ease with the tourists. The woman are ghosts; they hide from us and we only catch glimpses of the brightly-coloured combs which adorn the backs of their impressive afros, winking at us in the sunlight. They do not wish to be photographed. The children eyes us with bold suspicion, puffed out chests, dusty feet. They peer from their doorways, hanging on drapes of dirty sheets. They know their childhood is camera fodder, that they are sustained by the prying gaze of our lenses. They accept food; bags of crisps, sweets, chocolate bars, like animals in zoos: unsmiling, indifferent, resigned. But only the boys. The girls, more elusive than their mothers, are glimpses; shapes moving in the shadows. They do not leave their huts.

photographs from the jungle, Tamin Negara, Malaysia.

© Emily Hughes, 2019

Georgetown

Posted on March 22, 2019

I totally fell head over heals for Malaysia, especially Georgetown — as you can see it’s a photographer’s paradise, with its colourful streetart and crumbling colonial facades. Such a vibrant multi-cultural community, and everyone seems to live in peace and acceptance of one another’s faiths: Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Taoists and Buddhists are all represented here. There are so many temples and places of worship; on one street four Chinese temples stand literally within a stone’s throw of each other. You can visit most of them for free. We took a walking tour, but to be honest it’s just as fun to explore by yourself with a map. It was interesting to hear about Georgetown’s history though and our guide, Xavier, took us to the best street food spots. Every street you turn down has something interesting to discover and although it is touristy (particularly popular with backpackers), it still has a very laidback vibe and we didn’t find it too crowded, even in the height of summer. We stayed in a B&B on Love Lane, which is packed full of bars and restaurants and live music at night. Right in the centre of things — a great spot!

© Emily Hughes, 2019

Rain song

Posted on December 19, 2018

The slick sharp shapes of the city are blurred out of focus. The pale bright sky darkens. And then the rain comes. Sudden. Violent. An eviction. There is thunder. Lightning. I sit up. Turn my eyes to the sky, press my nose to the glass. There’s something thrilling about a storm which makes me feel like a child.

I listen to the rain pelt out tinny drum beats on the coloured metal roof tops. I wait. For it to wash everything away: dirt, sin, hope. I wait for it to end. I don’t want it to end. My eyes are bleary with colour block walls and mischievious gods with kohl lined eyes, scorpions which light up in the dark. Wary children with shy smiles and women who turn their backs to me, flashing brightly coloured teeth which nibble at proud whipped crowns. And banana leaves and teak trees, lush highland greens. Limestone mountains jutting into the sky. The electric blue of a birdwing butterfly. And smells I want to jumble up and strike onto hot night time pavements like firecrackers, inhale like anodyne: ripe melon, chrysanthemum tea, steamed yellow corn. Petrol and incense and ginger flowers. Fried banana doused in vinegar.

And the rain. I want to feel the warm rain on me. Sliding down my cheeks and the back of my neck, bouncing off my toes. I want the force of it to perforate me, punch me out onto an unknown landscape. I want to lean into it, let it prop me up, a cut out doll. I want it to drench my clothes to the outline of my flimsy body, dissolve me into a sugary puddle and suck my flip flops off my feet. I remember once, dancing in the rain. There was music. I was laughing, turning, my face and hands reaching to the sky, feeling the happiest I might have ever been. The rain can be a shelter for your loneliness. It can be freeing that way.

Outisde is all colour. Strange and rattling. But inside is quiet. Black and white. And it feels like I’ve slipped back into some watchful heart space, tender and fragrant as a kiss from a frangipane baby. I slouch against the cushioned seats. Soon, the roads are slushy canals. Sharp needles drill out dents in the pocked concrete. The downpour is exhausting. It slants across my vision, sends me into a cross-eyed daze.

We stop outside a restaurant. I see a group of men sitting and eating with their hands, bare foot, cross-legged. Flexing their toes like lizards.

It’s a slow crawl to the hotel, just 5o yards away. But no-one seems to mind about the hold up very much. No-one seems angry, or in a hurry. After all, they know. They’re no match for the sky around here. They wear patience on their sun-beaten faces like masks. A couple of horns beep pathetically and the rain drums on.

We shrug forwards and it calms, picks out a slower, more accidental rhythm. It builds again to the chorus, another unexpected rush of sound. A rising fury. Crescendo. This happens once, twice, three times.

A verse, a chorus, a song, of the rain.

© Emily Hughes, 2018, image and words.

jade

Posted on November 6, 2018

I love it when nature gives you such gifts of light and form and such vibrant colour as this. I have spotted these intriguing jade vines before in Brazil and I love the way they hang in curling tendrils like cascading waterfalls. I knew they would be perfect for some macro shots, but unfortunately I didn’t have access to my macro lens at the time. I was so happy to spot them again whilst on holiday in Malaysia this summer, in a butterfly farm in the Cameron Highlands. The light was perfect for creamy golden bokeh and rich vibrant colours so I whipped out my macro lens and spent a very happy half hour photographing them to my heart’s content. I haven’t really messed around with these because I didn’t need to; it’s all nature’s own grace and beauty.

More Malaysia plant life/street scenes to follow!

Emily

© Emily Hughes, 2018

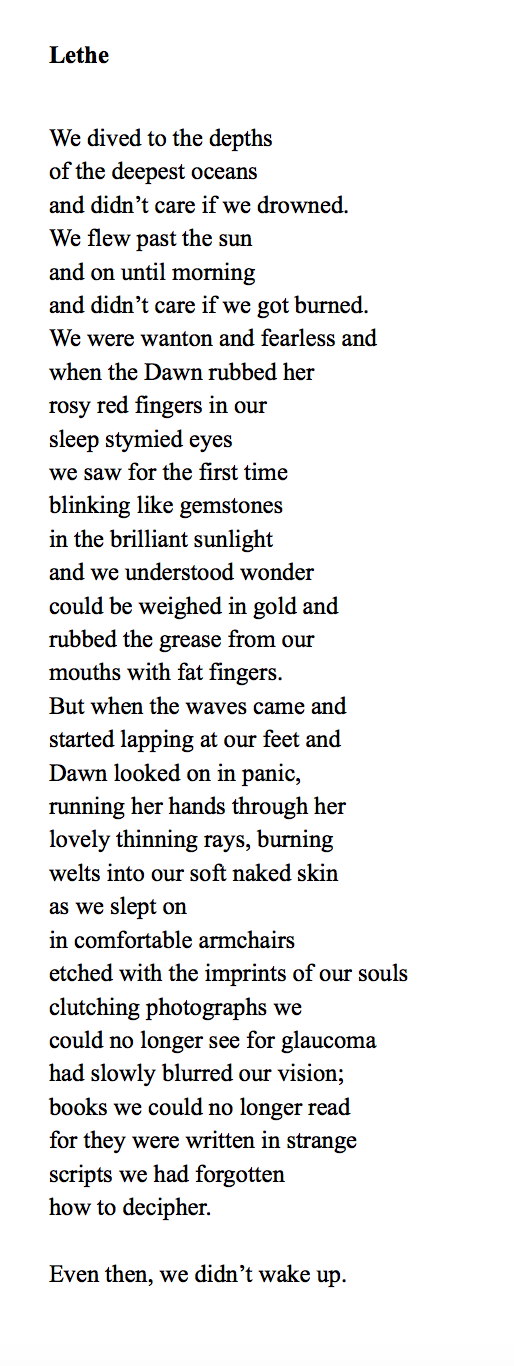

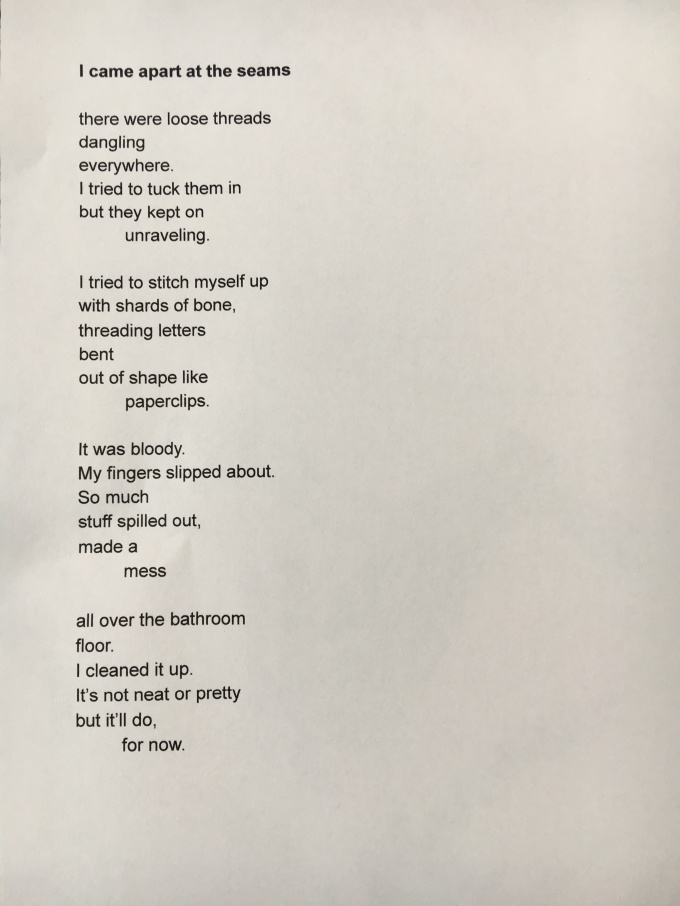

unraveling

Posted on October 10, 2018

It’s World Mental Health Day today.

Here’s a poem I wrote, for anyone who has unraveled at the seams. For anyone who has had to sop up the mess of themselves and squish it back inside and stitch themselves back up and, well, carry on.

If you are struggling right now then please, go to the doctors. Please reach out to people. Please seek help where you can. Because these battles of the mind are the loneliest and the darkest types of battles, and it takes an army to fight them.

Emily

© Emily Hughes, 2018

retreat

Posted on April 9, 2018

After a week on a writing retreat at the Hurst with Arvon I am feeling tired and exhilarated. So many thoughts and ideas spinning in my head. So many inspirational moments. So many wonderful, generous people.

There are countless benefits to a residential writing course and for each and every person the journey will be different; tailor made, if you like. But here is what I found: the freedom to retreat into myself and explore those spaces, the gaps, where the slices of light shine through. I found my voice, with gentle and insistent encouragement. I found that I had things to say with it. Things which are important. I found new friendships. And I laughed and sang and laughed some more, until tears rolled down my cheeks. Sometimes they were tears of happiness and sometimes it felt like there was something else being wrung out of me. Sometimes, I didn’t know the difference.

If you are thinking about doing a writing retreat I would highly recommend Arvon. Actually scrap that — don’t think, just book it! I promise you won’t regret it.

Emilyx

searchingtosee

searchingtosee